Solving 3D Headaches

Matt Brennesholtz Helps

Negotiate A Challenging 3D Future

By

Neal Romanek

(as printed in April 2009 TVBEurope)

“I love watching 3D, it’s just that after 10 minutes I have a pounding headache.”

At tradeshows, exhibitions, screenings, even meet-ups of 3D devotees, one hears it over and over. At the Digital Television Group's Summit 2009 in March, an overview of Sky's plans for 3DTV was introduced with "Here's Chris Johns to tell us about eye strain."

There has been a mad rush to produce 3D content even though their may not be the viewership for it. Critics vocally wonder if the producers of 3D content are living in a fool's paradise, preparing for The Next Big Thing that may never come. The Beijing Olympics was touted as the "3D Olympics". 3D trials were to play in limited markets, primarily in Asia. The fact that few people have heard that Beijing was the “3D Olympics” may suggest how successful the experiment was.

Creating dynamic, believable and commercially viable 3D images is a challenge that has been around longer than most people suppose. 3D is usually associated with the 1950's and the spate of anaglyph-based 3D feature films - although the anaglyph technique had been used to create 3D images since the 1850's. The first stereoscopic motion picture patent was taken out in the 1890's and the first 3D camera rig was patented in 1900.

TVBEurope talked with 3D expert Matt Brennesholtz, a senior analyst at Insight Media who has worked in partnership with the 3D@Home Consortium. The 3D@Home Consortium was formed in 2008 to speed the commercialization of 3D into homes worldwide. It also attempts to facilitate the development of standards, roadmaps and education for the 3D industry. In 2007 Brennesholtz co-authored a 400-page report “3D Technology and Markets: A Study of All Aspects of Electronic 3D Systems, Applications and Markets”. This all encompassing document forecast the viability of 3D display technology in a vast array of markets into the next decade. Its scope included not just stereoscopic 3D displays, but a variety of autostereoscopic displays, and rotating image plane, vibrating membrane, and micropolarizer technologies.

Brennesholtz is an expert in display technologies, having been a lead projection system architect at Philips LCoS Microdisplay Systems. He has a masters of Engineering in Optics and Plasma Physics from Cornell University and has been granted 23 patents. Still, we asked question most on everyone's mind - why do we get a headache when we watch 3D?

"One of the fundamental problems with 3D displays," he explains, "is the problem of convergence and accommodation." Convergence is the ability of the eyes to stay trained on a point in space and allows you to focus on the text on a mobile phone three inches from your nose. Accommodation is the ability of the eye itself to focus in distance like a mini-camera.

Stereoscopic images rely on the brain's default setting of always making a single image out of the pair of images received by the eyes - as opposed to how chameleons do it. The perceived "space" between the two side-by-side images in a 3D show is compensated for by convergence with the eyes going from being parallel towards being crossed and back - just as they would in watching a live event.

The element that is challenging for the brain - and for some viewers - is the image in a 3D display is always exactly the same distance away, on the surface of the screen. The convergence of the eyes sends the message that objects are moving forward and backward in space, but the real image each eye is capturing stays put. The brain is trying to tackle two different ways of seeing at once, like a computer running two memory intensive applications at the same time. The fact that the eyes are making very few focus changes, doesn't mean that the brain is not revving like an engine every time it thinks something is moving toward it or away from it. Perhaps, like the trick of being able to pat your head and rub your stomach at the same time, the brain may get the hang of it with repeated viewing.

"There can be other human factor problems associated with bad 3D displays," Brennesholtz notes, "with certain types of encoding, for example, but this is a fundamental problem that really is inescapable in the 3D display world."

The most serious aggravation of the accommodation-convergence discrepancy is when the content creator puts images in the virtual space in front of the screen - the monster reaches out to camera, the enemy fires a hundred arrows at us, and the like. These are the effects that producers may push because they have greater visceral impact, but they are also the things that most bother the eyes. Brennesholtz says the solution is to place most 3D effects at the level of the screen or behind it.

Another significant issue, one to induce headaches in content creators rather than viewers, is that the content has to be created for the screen size and viewing distance of the intended audience. Analogous to needing different sound mixes for DVD, theatrical, and mobile device content, each 3D version of a programme must be mastered with its final destination in mind. Sound mixers have managed complex sets of presets for each intended format, it seems likely that 3D mastering will have to learn to do the same.

Although some roadblocks to the perfect 3D experience are exactly the same as they were in the 1950's, Brennesholtz points out that the sophistication of today's technology may overcome the others. "Some of the other problems that have been associated with 3D, like dimness or differences in brightness and color between the two images, can be overcome with proper display, screen and video signal design."

Brennesholtz underlines the consumers demand for a quality experience that is the principle factor in adoption of 3D. “The end user, whether he’s watching broadcast television or cable or blue ray or is sitting in the cinema, is not going to give up anything to get 3D. He’s not going to give up resolution. He’s not going to give up frame rate. He’s not going to accept flicker. He’s not going to accept headaches. Basically, he wants his 2D experience – which right now when you look at HDTV is really good – but with 3D.”

Questions about 3D are in no short supply. Approximately 10% of the population are unable to properly see 3D, and what kind of a strategy must be developed when such a large segment of the audience must automatically be discounted? Most people are unaware that many TV's are already "3D ready", but where is the extra bandwidth going to come from if 3D TV is going to become a reality? And finally, if eyeball convergence and focus are such core issues in 3D viewing, what happens to the 3D experience after the third beer?

Labels: media production

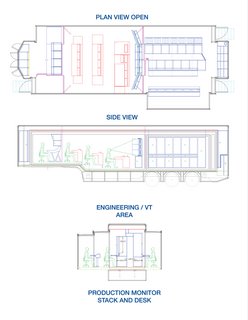

TVBEurope toured the vehicle as it was being systems integrated for its new Australian venture at the company’s European headquarters in Watford, UK. Gearhouse Broadcast’s trucks are coach-built by A Smith Great Bentley Ltd. HD-1’s project manager is John Fisher, who has been in the industry for over 40 years. HD-1 is the sixteenth truck John has built and he will start integrating number seventeen on behalf of Gearhouse Broadcast in the New Year.

TVBEurope toured the vehicle as it was being systems integrated for its new Australian venture at the company’s European headquarters in Watford, UK. Gearhouse Broadcast’s trucks are coach-built by A Smith Great Bentley Ltd. HD-1’s project manager is John Fisher, who has been in the industry for over 40 years. HD-1 is the sixteenth truck John has built and he will start integrating number seventeen on behalf of Gearhouse Broadcast in the New Year.

Though Robberechts is himself a broadcast industry veteran, he deliberately employs a youthful team of technicians, some straight out of Belgium's top film school, to help keep his edge sharp. "Some of these directors, the ones with the half-shaved face and expensive sunglasses, they are not going to speak the same language as me."

Though Robberechts is himself a broadcast industry veteran, he deliberately employs a youthful team of technicians, some straight out of Belgium's top film school, to help keep his edge sharp. "Some of these directors, the ones with the half-shaved face and expensive sunglasses, they are not going to speak the same language as me." Robberechts briefly expanded with the addition of a Paris office, but he quickly abandoned the foray. The current situation in Brussels was hard to improve upon. Brussels is, if you include English, a tri-lingual city. Its designation as the economic hub of Europe puts it at the financial and political center of things, and its geography allows rapid, easy access to Britain or anywhere in continental Europe via air or Belgium's straight, wide roads.

Robberechts briefly expanded with the addition of a Paris office, but he quickly abandoned the foray. The current situation in Brussels was hard to improve upon. Brussels is, if you include English, a tri-lingual city. Its designation as the economic hub of Europe puts it at the financial and political center of things, and its geography allows rapid, easy access to Britain or anywhere in continental Europe via air or Belgium's straight, wide roads. Kate Hopkins and Tim Owens work out of their Bristol-based company,

Kate Hopkins and Tim Owens work out of their Bristol-based company,  "Obviously, most of 'Blue Planet' is underwater. It could have been just music and a general underwater track. But we decided, between the producers and the sound editors, that we were going to go for something different, because no one knows what you could actually hear underwater. There are some very natural sounds that you hear – humpback whales and shrimp clicking. But I added some much bigger noises – the fish going past – because it just adds to the strength of the images. And then there were some very tiny creatures too that I added some very strange, very designed noises. Whether it was real or not, I'm not sure that that mattered. It worked with the picture."

"Obviously, most of 'Blue Planet' is underwater. It could have been just music and a general underwater track. But we decided, between the producers and the sound editors, that we were going to go for something different, because no one knows what you could actually hear underwater. There are some very natural sounds that you hear – humpback whales and shrimp clicking. But I added some much bigger noises – the fish going past – because it just adds to the strength of the images. And then there were some very tiny creatures too that I added some very strange, very designed noises. Whether it was real or not, I'm not sure that that mattered. It worked with the picture."