The term “transmedia” seems to have originated in 1991 with Marsha Kinder, the critical studies dynamo of USC’s cinema school. When I was at USC, cinema students were divided into two theoretical camps. You were either a Marsha Kinder devotee (European, experimental, theoretical cinema) or a Drew Casper devotee (classic American cinema with big movie stars). And I have to say it was Drew Casper for me at the time. But I was young and narrow-minded. Today it would be Marsha though, definitely.

MIT gave “transmedia” its seal of approval in 2003, when Henry Jenkins – also a USC media professor now – wrote his game-changing article “Transmedia Storytelling”. I’ve always thought that knowing the names of things is one of the differences between an amateur and a professional. But the terminology is still flux when it comes to 21st century media. We’re making this stuff up as we go, and it will take some time to get our toolboxes properly organised. In the present Tower Of Digi-Babel ruckus, some people say, “transmedia”, some “crossmedia”, some “media 360”. Me, I say “full spectrum media”. Richard Wagner said “Gesamtkunstwerk”. And people in 1999 said “new media”.

The key feature that distinguishes true transmedia from stories presented discretely in traditional formats is that in transmedia, the story exists before and beyond its appearance in a specific form. I’d like to think that the pen & paper role-playing games of yesteryear were one of the first truly transmedial entertainments, where characters, places, monsters and events are assumed to already exist and the stories experienced and told by players are spin-offs and riffs on the already existing world. Some of the major science fiction franchises too have offered up stories, characters and worlds that appear transmedially, as children of the original universe. But we are still in the Wild West phase of transmedial storytelling and transmedia is yet to fully stand on its own two – or three or four or twelve – feet.

Last September, I attended one of the most important conferences of the year for European media professionals – Transmedia Next. The three-day event took place in London – in a lovely Thames-side corporate building, halfway between the Tate Britain and the Houses Of Parliament – and was hosted by transmedia pioneers Seize The Media. It featured lectures, discussions and exercises facilitated by a full spectrum of transmedia expertise – Seize The Media’s CEO Anita Ondine, the company’s Chief Technical Architect David Beard, and its award-winning Story Architect Lance Weiler.

Providing intellectual backbone to the Transmedia Next conference was media expert and educator, Inga von Staden. She is director of the Interactive Media programme at Berlin’s Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg and also directs the MEDIA training program at the Media Business School, Spain. She works first-hand with visionary creatives who are in the process of inventing 21st century media. She has been a guiding force in moving them forward and has, as often, learned from them what transmedia really can do.

I had the good fortune to interview Inga von Staden about her work and the past, present and future of 21st century media:

NEAL ROMANEK: So how do you answer when someone asks you “What IS transmedia?”

INGA VON STADEN: I tell them it is one of several terms used in the converging media landscape. “Transmedia” was coined by Jenkins (and Kinder—NR) focusing on a story to take the user through different media platforms. The other terms currently in use are “crossmedia” which was coined by the advertising industry, referring to integrated, cross-platform campaigns. And there’s also “360Degrees” which refers to a theme playing out across a multitude of platforms and also includes factual content that may be less story-driven than fiction. 360Degrees is quite popular term in the European media industries.

NEAL ROMANEK: You started out as a filmmaker. How did you get to where you are now?

INGA VON STADEN: I began working in television and film productions in 1987. In 1995 I migrated into games and internet development as a conceptor and project manager. Then I worked as a consultant for the media industries from 1999 to 2008 helping with the paradigm shift from analogue to digital. My clients were print publishers, tv broadcasters, and also the film industry.

The more I worked with these companies, the more I became aware that there were too few professionals who could do the work that converging media implied. So in a lecture I gave at the Bertelsmann Association in 2000, I proposed we change our narrowly focused film education to a wide media education to create professionals who develop and produce content for all media platforms. My proposal was not particularly well-received at the time. But ten years later the director of my film school wrote in the school’s studies guide: “360Degrees is the new magic term.” I do not really think it is magic, but I do think it is a very sensible approach to the media business.

In 2002 I set up Germany’s first European MEDIA programme, “The Academy of Converging Media”, training authors and designers to think transmedially. And I wrote the first national studies on digital cinema for the German Film Fund in 2002 and 2003 . Today I run a four-year diploma studies programme at the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg (www.filmakademie.de) dedicated to 360Degree Media. Our students are trained to work as transmedia producers and transmedia content directors.

Now, apart from giving lectures at conferences, hosting seminars and directing the studies program mentioned above, I coach interdisciplinary teams through the transmedial development process. It is very stressful to be suddenly doing what you have always done your way with others who do it their way. We see this even when we bring together students from different departments or schools in our Content Labs. But the innovative force that is unleashed once the communication and methodology have been practiced is simply amazing.

NEAL ROMANEK: And you became involved in Transmedia Next how?

INGA VON STADEN: For the Transmedia Next conference, I was contacted by Anita Ondine, who had heard of me through European MEDIA training programs on converging media.

NEAL ROMANEK: So is there any going back to the traditional, 20th century way of doing things for you? Or do you see yourself now permanently operating in a multi-platform world?

INGA VON STADEN: Once I began seeing ideas, stories and themes through the transmedial lense, I found it very hard not to make transmedial suggestions when involved in a development process.

NEAL ROMANEK: What are the most difficult parts of the creative process in constructing transmedia material? What are the unique challenges that are not present in producing other content?

INGA VON STADEN: To go transmedial means you have to allow for a pre-development. In other words, before you develop a format – a film, a game, etc. – you must first develop the story universe that will be the foundation on which all the different media formats will be based. This concept of pre-development is not usually taken into consideration in the development process of content. Or in the budgets for the development process. Furthermore, you have to change the process to be less linear. Transmedia is much too complex to be designed by just one person. It is a team-oriented pool process. The producer needs to bring in other disciplines to participate through the entire development process – a technical director, for example, and a community manager. And the content director needs to be educated in all media formats to understand the input they’re getting from the different team members.

Transmedial projects tend to become very big and complex. The art is to allow for all the possibilities that transmedial thinking can offer to come into the brainstorming sessions at the same time, and to structure the development process along a commonly accepted methodology, ie the “content onion” by Raimo Lang (YLE). You have to consolidate the content into an operative idea – the creative kernel – and from there build the red thread through that story universe the team has designed. The art is to keep it simple.

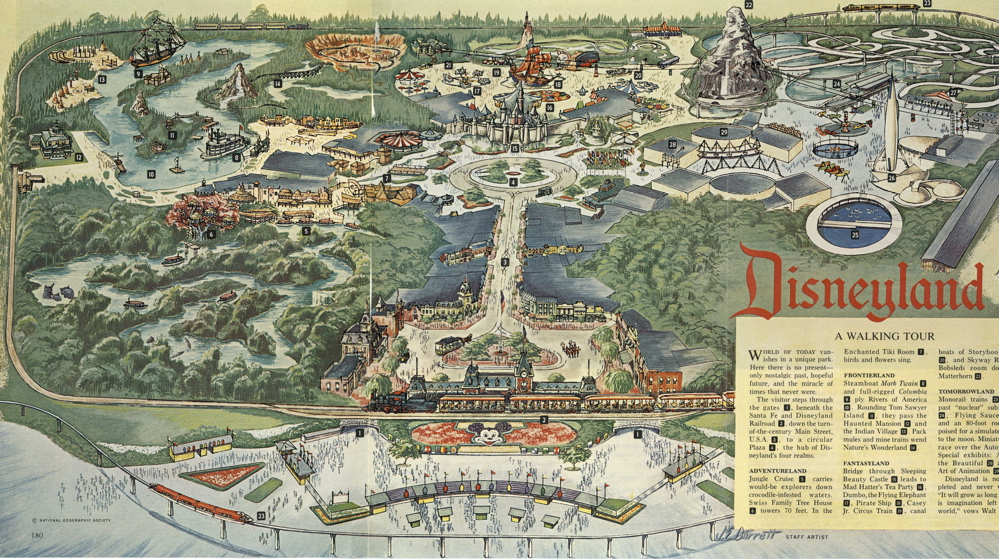

NEAL ROMANEK: How is today’s transmedia different from past efforts at presenting a story across multiple platforms? How does it differ, say, from what Walt Disney was doing with simpler technologies 50 years ago?

INGA VON STADEN: Transmedia is more than just crossmedial distribution. Transmedia is understanding an story or theme to be more than just a film or game or an app. It is about the notation of the story universe that an author has in his head as he writes a story. By exposing that story universe, the team members and co-production partners can share in it and become part of the creative process. They can collaborate to design a media architecture that will take that idea or story or theme across different platforms. This is not about a film going onto the internet or a character being merchandised, though that could certainly be part of the design. It is about understanding what part of the idea, story or theme plays best where and how the different media formats are interlinked, via “rabbit holes”, portholes into the various spaces within the story universe. Simple examples are having the main plot of a story happen in a TV-series and different sub-plots staged on the Internet. Another example might be opening up spaces in the story universe to users who will create user-generated media to feed into the overall content.

NEAL ROMANEK: Whenever I talk to producers about transmedia, there often seems to be the same response – and said with quite a lot of confidence: “There isn’t any good way to make money from it”.

INGA VON STADEN: Transmedia is more expensive than “simply” making a film, game, app, or building a community. But each format in a transmedial architecture will be cheaper than if it had been produced on its own. You create synergies, production resources that can be reused and reconfigured. So rather than making 5 films for the sum of X, you are creating 5 different formats for the sum of X minus Synergy.

And furthermore we are seeing film producers having an increasingly hard time to come up pre-financing. So thinking transmedially, you can create content that feeds into another platform and then cross-finance your film with those revenues.

There is no one business model. There are many business models out there. Each media platform has its models for making money. They would otherwise not exist. Now you will probably not be making money by uploading your film to YouTube – a film does economically much better in a cinema, on DVD or VoD-platform. But you may make money selling elements of your story universe on a pay-per-item basis and collecting micro payments from an online community. A transmedial producer must creatively combine the financing and revenue models out there to come up with a project’s very own business model. I call it the transmedial business mash-up model.

NEAL ROMANEK: What is the biggest potential growth area for transmedia? Entertainment? Marketing? Education? And where is the best transmedia work being done today?

INGA VON STADEN: Transmedia will most likely be making its big money with entertainment as most media does. But we are currently seeing the most interesting projects come up in the factual realm born out of the necessity of documentary film companies to find new business models in order to survive. Examples are “Prison Valley” or “The Galata Bridge”. And we have seen transmedia happen for years already in children’s media. Kids find it so easy to surf a story environment on different platforms.

NEAL ROMANEK: I feel like transmedia now is in the same place as movies were in the 20th century. Movies imitated past popular media, like novels and theatre. A lot of transmedia seems to imitate movies. How do we get away from imitating movies?

INGA VON STADEN: You soon become more creative than simply emulating the movies if you bring in different disciplines into your creative team. A game designer has a very different approach to content, as does a designer of apps or a builder of communities. Take a look at the great work Dr. Randy Pausch (creator of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University) did with his “Building Virtual Worlds” class.

NEAL ROMANEK: How can transmedia creators help each other?

INGA VON STADEN: Share experience and build a body of professional knowledge! That is the only way we can all begin making interesting projects and earn a living with them.

—