I joked about mistaking William Goldman for his brother James in a post about the Screenwriting Expo, but I do adore James Goldman‘s two medieval movies, “The Lion In Winter” (1968) and “Robin and Marian” (1976) and, although it is harder to fail when you don’t work as much, I think elements of both films are superior to Brother William’s best screenwriting work.

I joked about mistaking William Goldman for his brother James in a post about the Screenwriting Expo, but I do adore James Goldman‘s two medieval movies, “The Lion In Winter” (1968) and “Robin and Marian” (1976) and, although it is harder to fail when you don’t work as much, I think elements of both films are superior to Brother William’s best screenwriting work.

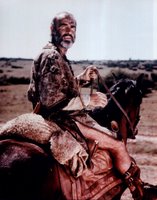

I like period movies too, particularly those that execute medieval settings well. I’ve studied “The Lion In Winter” (1968) for years, but I went back to it, and to “Robin and Marian” (1976) also, when I was writing “Fortune and the Devil”. Both scripts are breathtaking – “The Lion In Winter” for its staggering dialog, “Robin and Marian” for its romance and heroism.

I like period movies too, particularly those that execute medieval settings well. I’ve studied “The Lion In Winter” (1968) for years, but I went back to it, and to “Robin and Marian” (1976) also, when I was writing “Fortune and the Devil”. Both scripts are breathtaking – “The Lion In Winter” for its staggering dialog, “Robin and Marian” for its romance and heroism.

Because his more famous brother has shone more brightly, we don’t often hear James Goldman’s take on the screenwriting life. So I thought I’d offer up an excerpt from his introduction to the published version of “Robin and Marian”:

“The screenwriter is anonymous and why this is so is worth talking about. There are, it seems to me, two basic reasons why, one of them historical and the other dumb-headed.

Historically, movies don’t seem to have had writers at all. I’m speaking, of course, of the silents. Someone, obviously, had to write the captions, just as someone has to pen the instructions that come with your dishwasher. But it’s as difficult to give some writer praise or credit for “Intolerance” (1916) as it is to think of the creator of a Christmas pantomime as a playwright. Writing, we are prone to think, is words.

Not so. Aristotle, who is a permanent hero of mine, took the position that the elements of a play, in order of importance, were: plot, character, thought and then – and only then – diction. Now, movies are a branch of drama and a screenplay is a kind of play and on the screen you don’t need words to tell a meaningful story about fully realized people. “City Lights” works without its captions. Though wordless, someone wrote it. But the point is, watching it, we feel that no one did. Movie writing came in through the back door. And it stayed there.

Why it stayed there also has to do with words. I’ve got to confess that I was in my early teens before it occurred to me that someone actually wrote a movie. Tom Mix was a real man and he rode up on a real hore to a real corral. And when Tom spoke, it seemed like he was speaking for himself too. Nobody wrote that ‘Howdy’. He just up and said it.

If he sang it, we’d know different. For while singing is a natural thing, the invention of melody is not something most of us can do. But inventing sentences?? We’re all like Moliere’s ‘Gentilhomme’: we’ve made the staggering discovery that everybody speaks in dialogue.

Or, put it this way. Improvising at the piano seems slightly miraculous. How does the fellow do it? But improvising dialogue occurs every time one opens one’s trap. The inevitable result is that most of the conversation we hear in movies sounds to everyone – except the writer – as if nobody wrote it…

We also know the words aren’t improvised when the dialogue sounds, in one way or another, composed. I have in mind not only Bible epics – no one ever talked like that – but writing that is noticeably witty, stylish or complicated. ‘Notorious’ seems ‘written’, ‘Bullitt’ does not: Steve McQueen seems to say whatever comes into his head, but Cary Grant is working from a script.

So by and large, the film writer is unknown because his work seems unwritten…”

Or should seem unwritten, if he is doing his job.